Field journaling

Practice writing down and drawing observations in a playful way to make science and note-taking easy.

Overview

In this activity, students will use freeform field journaling to engage with nature and record their observations. You’ll start with a conversation to better understand the value of writing scientifically versus writing in a personal way that makes sense for you. Then students will go outside and use writing, thinking, and drawing to record and share their observations about the world around them.

For a more structured activity for younger students, see Nature journal (Grade 3) activity.

Instructions

What you'll need

- Each student will need:

- A pen or pencil

- Paper or a notebook

- Optional: You may choose to provide the following for the class to share.

- Tools for measuring and observing like rulers, magnifying glasses, and small weights

- Pencil crayons or markers

Opening discussion

- Open up a discussion about notetaking and memory. How do you take notes during a class or presentation?

- Discuss how paraphrasing and shorthand helps you to take notes faster

- Discuss how memory is important—not just remembering exactly what was said but remembering how it connected with other concepts in class and your own thoughts, feelings, and epiphanies. In many cases it’s helpful not to record things exactly as they were said.

- Discuss that in most situations, notetaking is personal and you can choose the best way to remember something.

- Ask the class how you can remember something you observed—for example an object in the classroom.

- The students might say photos, and this is a very helpful tool. However, emphasize that taking a photo might not be as engaging as making your own observations.

- Discuss what senses you might engage and write about: Sight, sound, smell, touch, and sometimes taste.

- Optional interactive: To get students engaged with their senses, share a stimulating item with them, like a fragrant snack or a scented candle. Follow-up by asking them to raise their hand and share how they would describe or remember the item you passed around.

- Discuss the difference between scientific/objective observations versus personal/subjective observations.

- Using standardized measures helps when you need to share information. For example:

- A piano key hits a specific note like B sharp.

- Colours have specific names like Indigo

- Animals have scientific names to catalog them for observation. For example, we would see what we call a crow, but technically a crow is a genus of animals and there are many species called crow. The ones we observe in B.C. are usually the Corvus brachyrhynchos or the American crow.

- When communicating with people around you or recording things for yourself, you probably use what means the most to you.

- The smell of a flower bouquet might remind you of a place you went on vacation to.

- A bite of food might taste good or bad to you, and you might tell your friend to eat it or avoid it.

- There are also shared cultural observations. People from the same place have shared points of reference, like how Vancouverites might associate sand with Kits Beach. There are cultural sources of meaning, for example Indigenous nations in B.C. and beyond connected animals to personality traits and virtues.

- Both scientific and subjective observations are valid and have times they are most useful. When taking notes or journaling, use what comes natural to you and helps you remember things—but you can also experiment.

- Using standardized measures helps when you need to share information. For example:

- Conclude by letting students know that they shouldn’t be afraid to express themselves or use what makes sense to them when it comes to personal notetaking and journaling. They might even find unique ways to share with others from a new perspective.

Introduce the activity

- Share that the class is doing a field journaling activity. Field journaling is about recording observations in a way that engages with your subject, helps you to think about it in detail, and helps you to remember what you saw. This is especially useful in natural settings like the forest. There are three key elements to field journaling: Drawing, writing, and thinking—see Teaching notes for more insight.

- Ask everyone to gather their supplies for a field journaling session. You might ask them to bring specific supplies like a pen and paper, or you might invite them to bring whatever they want to use. You could also choose to distribute new supplies for this activity or bring supplies outside for them to choose from as they go.

- Optional: You may wish to provide some tools for measuring and observing, such as rulers and magnifying glasses.

- Optional: You may wish to provide some tools for measuring and observing, such as rulers and magnifying glasses.

- Bring the class outside for a field journaling session.

- Being near a forest or a thicket of trees is ideal, but make sure it’s safe area.

- Set boundaries so that the class stays in an area.

Journaling session

1. Start with a guided journaling exercise where everyone will participate. Gather around an object that’s big enough for everyone to see, such as a large tree or a bed of flowers.

- First, get everyone to observe the subject from a distance. Ask them to start journaling about the subject: Record observations, draw and write how they would describe it, and think of how they’d compare the size to other things. Make guesses about what you’ll see when you look closer.

- Next, get everyone to walk up close to the subject. Encourage them to lean in very close or look at a parts of it in detail. Ask them to record this too: Draw and write about what new details they see.

- Finally, ask the class to write down things they know, feel, or wonder about the subject if they haven’t already.

- Do they have any prior knowledge? How does it make them feel? What questions could they ask about it, and do they have any theories about it?

- Finish by inviting everyone to share their findings. Invite them to connect their journaling with other students or compare their differences.

2. After the guided session, make time for a freeform session where everyone can split up and make their own observations.

- Let the class know how much time they have and the boundaries to stay within.

- Circulate and encourage them to use a mix of writing and drawing while also recording questions and theories.

- When time is up, get into a circle and share what everyone journaled about.

- Optional discussion: Consider finishing with a conversation about all the details students observed in the area, and think about the impact that development and construction would have on all the elements of the ecosystem.

3. When the journaling activity is done, make sure everyone leaves the area as they found it and brings their supplies back to class with them.

Optional follow-up:

- When you get back to class, make time for the class to reflect on the exercise. Let students raise their hand and share how they felt about the journaling and if it inspired them in new ways. Students are encouraged to think about how field journaling can make it easier to approach research and writing by starting with what feels most natural to them.

- The next time the class takes notes such as during a movie or presentation, remind them of the field journaling activity and encourage them to apply some of those principles to their notes.

Modify or extend this activity

- To compare freeform journaling with academic writing, make it an assignment or homework to turn the notes from the journaling session into a report. This could involve rewriting the notes in a more formal way and including high quality images found online, or it could involve explaining the process and logic behind their journlling in a short essay while reflecting.

- Consider giving everyone a fresh notebook for the field journaling activity and getting the class to bring it out and use it for notetaking again throughout the year.

- As homework, ask everyone to do a page of field journaling in their yard or in one of their favorite places and then share it with the class the next day.

Curriculum Fit

Core competencies

Communication

- Acquiring and presenting information

Thinking

- Evaluating and developing

- Analyzing and critiquing

- Questioning and investigating

Personal and Social

- Identifying personal strengths and abilities

- Contributing to community and caring for the environment

Science 4-6

Curricular Competencies

Questioning and predicting:

- Demonstrate curiosity about the natural world (Gr. 4)

- Observe objects and make predictions in familiar contexts (Gr. 4-6)

- Demonstrate a sustained curiosity about a scientific topic or problem of personal interest (Gr. 5)

Planning and conducting:

- Safely use appropriate tools to make observations and measurements (Gr. 4)

- Make observations and collect simple data in the local environment (Gr. 4)

- Choose appropriate data to collect to answer their questions (Gr. 5-6)

Processing and analyzing data and information:

- Experience and interpret the local environment (Gr. 4-6)

- Compare data with predictions, develop connections and explanations (Gr. 4-6)

- Demonstrate an openness to new ideas and consideration of alternatives (Gr. 5-6)

Communicating:

- Represent and communicate ideas and findings in a variety of ways (Gr. 4)

- Express and reflect on personal or shared experiences of place (Gr. 4-6)

- Communicate ideas, explanations, and processes in a variety of ways (Gr. 5-6)

Assessments

- Observe students' engagement with the activity and willingness to journal and share.

- Assess students' participation when discussing and sharing each other's work.

- Assess journal entries for effort spent and engagement with observed subjects.

Teaching Notes

Compared to other activities, the challenge with field journaling is not just guiding students to accomplish it correctly but to spark their imagination and give them the confidence to journal their own way. A key point to share with students is that writing and science are a process, and that it starts with simple things like taking notes and drawing things you see. They should feel empowered to journal instead of striving for perfection.

It can help to break the activity down into prompts and examples to get students started. Field journaling involves three key elements:

- Drawing: With field journaling, it’s usually a good idea to do some drawing. This helps you to record visual observations and think about what you see. You do not need to be a skilled artist, and you can use playful ideas to record something.

- For example, you might have a hard time drawing an animal you see, but you can still record shapes, textures, and comparisons to other objects. If you compare the lizard to a five dollar bill, how big is it?

- You don’t have to capture everything in your drawing—you might draw a simple tree but draw certain elements like the bark in more detail.

- Drawings can help emphasize things you want to remember in a way that photos don’t. For example, you might draw sparkles on a river to emphasize how clean and clear the water was, or you might draw dark ripples on some bark to emphasize how rough the texture was.

- Writing: A field journal should use writing to help remember what your thoughts were when filling it out. That said, you should avoid the instinct to write in detail or to capture it perfectly like you would in an essay. Instead, use writing to record important observations. You can use a mix of long sentences and short words—in any way that makes sense to you.

- Thinking: Your field journal is all about using mediums and methods of your choice to think and engage with what you see.

- Observations—record what you observe with all your senses so that you can remember, research, and compare later.

- Questions—don’t be shy about recording your thoughts and acknowledging what you don’t know. Questions like: what is this bug called? Why is the water in this creek orange like rust? How did moss get up so high?

- Connections—connecting your observations with things that are familiar or you already know can be a great way to remember. Examples: I remember this flower from my mom’s garden; we talked about this place in class; that boulder is bigger than a car.

- Theories—Use your observations, thinking, and connections to start finding ways to explain what you’re seeing. For example: You learned in class that the wind can carry seeds around, so you suspect that’s how the dandelions reached this field; there are lots of bees buzzing around, so there are probably lots of flowers nearby.

- While you’re journaling, you don’t need to have all the answers and your theories can be as likely or as unlikely as you want. Just make sure you are mindful of where your theories come from—if you have a strong theory based on what you learned in class then it’s worth sharing with others; if you think a bug is so weird that it might have come from another planet then you can hold onto that theory until you find better evidence.

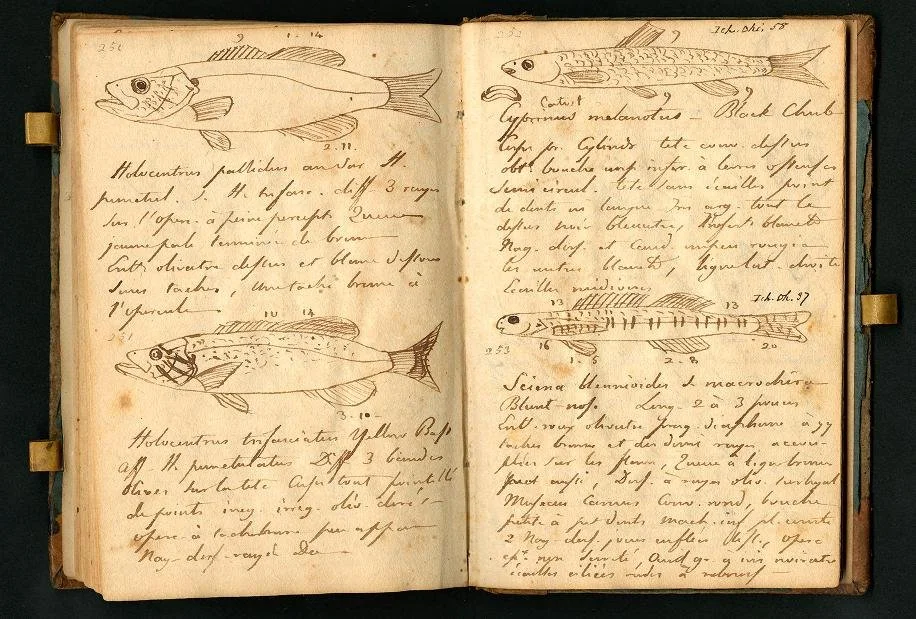

History of field journaling

It’s not easy to pinpoint where field journaling begins as a practice. Some field notes in history may look formal by today’s standards so we wouldn’t think of them as field notes. Likewise, thinkers of the past may have done observations in the field then written notes down at home—especially if heavy papyrus and inkwell pens made writing outdoors inconvenient.

Field journals may not always be clearly defined in history, but what’s important for students to understand is the power of making observations and engaging with a subject while also understanding that there are different ways to record something—it can be full sentences and intricate drawings, or it can be shorthand notes and rough doodles.

Field journal kept by Constantine Samuel Rafinesque in the early 19th century. (Image source: Exploring Overland)

There are different elements that make field journaling happen:

- Literacy – language enables and shapes journaling. In the past, only a small percentage of people knew how to write and could participate in journaling. In cultures where knowledge is passed orally, it would be important to share findings with others and to remember them so that they can be shared.

- Tools – Nowadays, anyone can buy a pen and some paper. These tools weren’t always widely available, and early iterations like papyrus and quill pens would be harder to use in the field. Notetaking in the past would have been

- Location – Field journaling works best in proximity to nature. It can be used for any setting, even urban areas, but it tends to be most effective for documenting observations about natural settings. It’s also important to feel safe to stop and journal about observations, whether you’re in a safe environment like a city park or whether you have a group with you to stay safe from predators in rural settings.

These elements solidified together most in the 18th and 19th centuries. Possibly the most famous example is Charles Darwin, whose field notes about birds on Galápagos Islands are often used as an introduction to evolution. That said, it’s important to remember that things like paper records can easily be lost to time, especially if they were considered less important to preserve at the time. For example, writers and thinkers in history may have taken notes in the field but discarded those after they wrote more formal books and notes which were better preserved. Before writing became a common way to write down your thoughts, oral history would have been an important way to record your observations.

Field journaling and conservation

Field journaling in the classroom context is a tool to learn about nature while practicing notetaking and critical thinking. That said, field journaling also connects with practical applications in the workplace and beyond. The skills developed in this activity transfer to many contexts, whether that's conducting studies in natural settings or notetaking in a workplace. Nature journaling specifically is an important step for any company or organization that needs to study ecosystems.

For students who want to get involved with environmental activism, field journaling is a great exercise to open up their imaginations. The most important starting place in conservation is to document what needs to be protected and how everything in an ecosystem is connected, and the best way to start is by visiting a place to document what you observe. Field observations can be adapted into a letter or petition to local representatives, or into an action plan for conservation work.

BC Hydro conducts impact studies before any new construction so that we can account for and mitigate impacts on local plants, wildlife, and populations. Part of this process involves visiting the site and making sure we understand the local ecosystem so that we can protect it as much as possible. Students who are keen observers and have a passion for the environment should know that there is a place for these traits in BC Hydro and other organizations.

Other resources

- John Muir Laws website

John Muir Laws is an expert and leader in the art of field and nature journaling. His website features plenty of great resources to dive into the subject. - How to Teach Nature Journaling book by John Muir Laws

On his aforementioned website, John provides his seminal book on the subject as a free PDF download. You can also purchase a physical copy, which is ideal for students to look through and draw inspiration from. - Field journaling 101 lesson (PDF)

This short printable guide created by Teton Science Schools is a great introduction to field journaling and may be useful to provide to each student as a reference.