B.C.’s hot springs go kilometres deep in quest for hot water

As a resident of the world’s so-called Ring of Fire - the seismically and volcanically active land around the Pacific Rim - British Columbia boasts the majority of Canada’s hot springs, with more than 85 in this province. But we’re a bit of a lightweight compared to some other Ring of Fire nations.

Idaho has more than 250 hot springs. And Japan, roughly half the size of B.C., features about 4,500 springs ranging from cold to very hot. B.C. is still a fantastic place to visit hot springs, and for geologist Glenn Woodsworth, they’re the source of a decades-old passion that has produced countless expeditions to hot springs both wild and tamed – and three editions of what is the hot springs bible in these parts: Hot Springs of Western Canada.

“For me the adventure is just getting there, checking out a hot spring, maybe collecting some samples for water chemistry,” says Woodsworth, who co-wrote the most recent version of the book with his son David. “Soaking for me is secondary. I’m more into the intellectual side of things.”

It turns out that the intellectual side is fascinating, starting with the basics of how they work, why it’s been difficult to harness geothermal power for electricity generation in B.C., and ending with the amazing. Did you know that flowers can bloom year round in some B.C. hot springs, and that a snail living at Banff’s hot springs lives nowhere else on the planet?

Hot tip! If you want to get the most out of a hot spring, visit one in the cold of winter, when crowds are fewer or nonexistent, and when the unique ecosystem – perhaps treating you to a blooming flower or two - can be fully appreciated. More on that later. For now, let’s tackle the science.

Skookumchuck Hot Springs are popular year round and are located a two-hour drive north of Whistler near Lillooet Lake.

Skookumchuck Hot Springs are popular year round and are located a two-hour drive north of Whistler near Lillooet Lake.

(Photo copyright Glenn & David Woodsworth)

Going deep – as in really deep – on the geology of hot springs

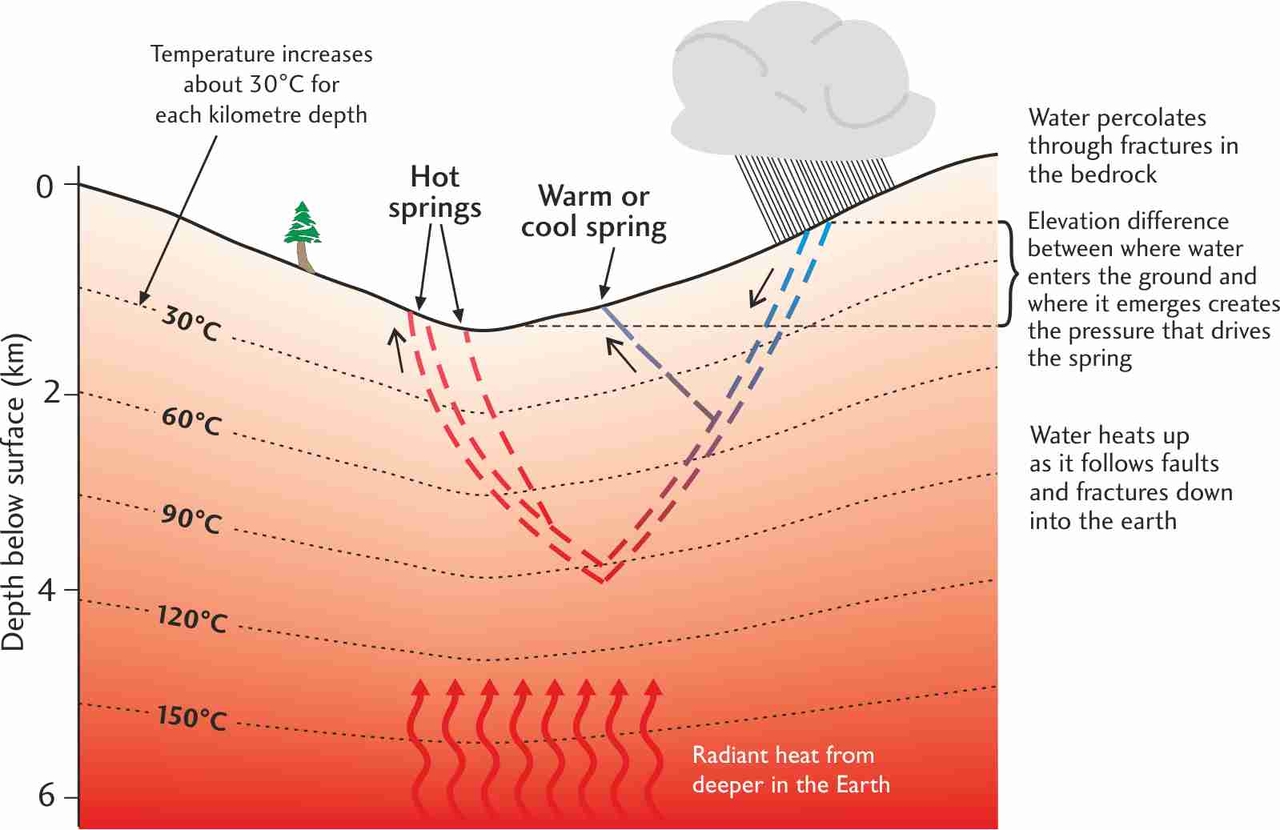

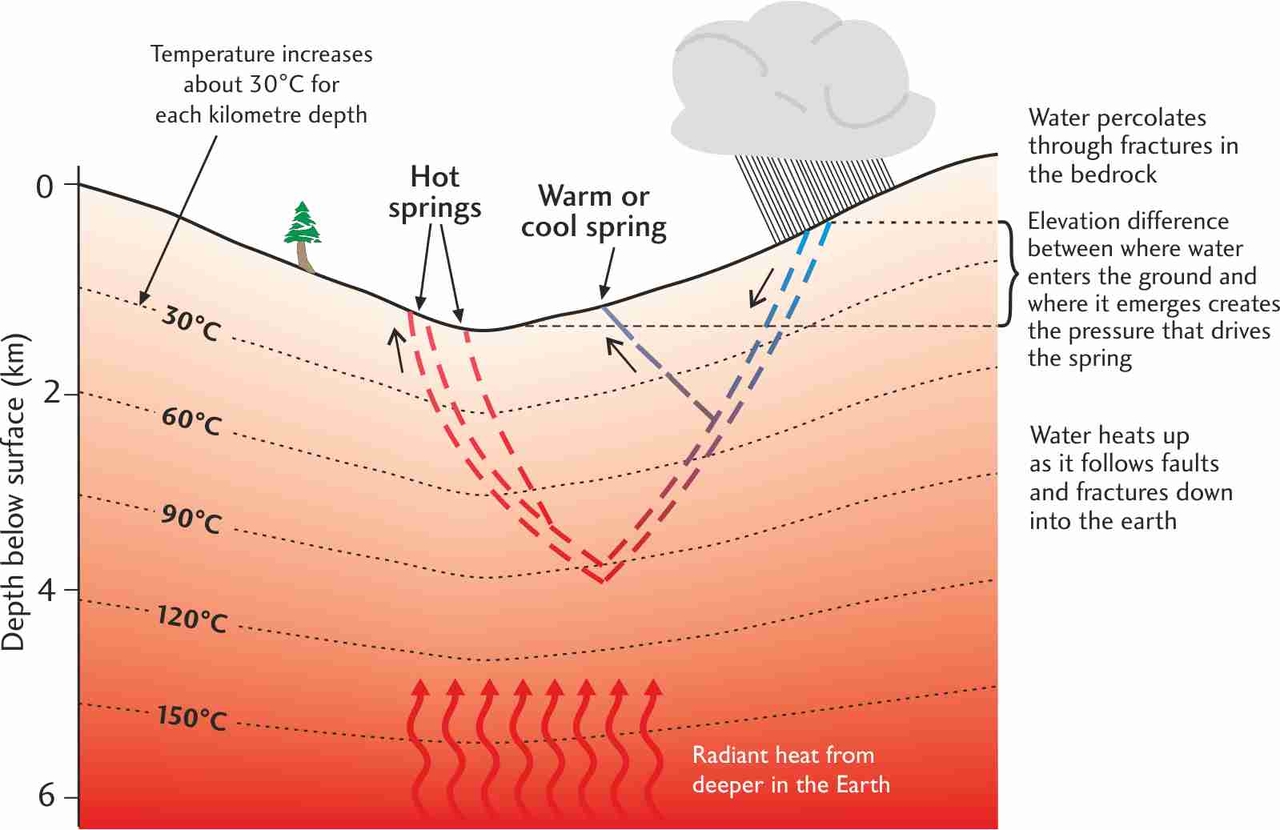

If you guessed that hot water in a hot spring is just hot water from the depths of earth that bubbles up to the surface, you’d only be half right. That water started as rain or snow on the surface, made its way through cracks and fissures several kilometres deep, then got pushed back up.

“The heat comes from two sources,” says Woodsworth. “There’s stuff that’s left over from the formation of the earth itself, known as primordial heat. And the other part is due to the decay of radioactive elements: uranium, thorium and potassium. Whenever these atoms decay, they give off radiation and heat. That’s where the heat’s coming from.”

The level of radioactivity the water of most hot springs is so low as to be no danger to our health, although it’s not a good idea to drink the water, which can harbour bacteria and dissolved metals. “In effect, hot springs are to some extent nuclear powered,” he says. “It doesn’t mean that the water is radioactive. It’s just that the heat is produced by that radioactivity.”

Springs in B.C. range from icy cold to temperatures in excess of 80°C, far above what is safe for us to soak in. Most, however, are in the comfortable range, and many vary in temperature depending on how close to the emergence of the hot water you choose to soak.

There are three things required for a hot spring: water from rain or snow, fissures or cracks that form a “plumbing system” for the water to circulate and then emerge from the earth, and the heat source way down.

In Western Canada, the temperature of the earth increases about 30°C for each kilometre of depth. Rock three to four kilometres below the surface is above the boiling point of water, but the water that emerges to the surface cools along the way, in part because of the distance travelled, and in part by mixing with cool water at or near the surface.

How does the water get back to the surface? Here’s how the Woodsworths explain it in their book:

Two processes can drive this heated water to the surface to form a hot spring. The first works because water runs downhill. Gravity feed, or artesian flow hot springs, rely on a plumbing system where the cold water enters the ground at a higher elevation than where it exits.

The other process is called thermal convection. It occurs because hot water is less dense than cold water, and thus tends to rise towards the surface. This difference in density sets up a giant convection cell, which is kept going by additional cold water percolating into the ground to keep the plumbing system fill with water.

Want to see how that convection works? Try this experiment, but make sure you do it in an area that can get wet.

(Diagram copyright Glenn and David Woodsworth)

(Diagram copyright Glenn and David Woodsworth)

Mount Meager and the quest for geothermal electricity generation

Between 1975 and 1982, BC Hydro drilled two holes in the Meager Creek area, the site of an extinct volcano, that went 3.5 kilometres below the surface and discovered temperatures of up to 200 C. The idea was to explore the possibility of a geothermal power plant, where hot water rising to the surface would produce steam to drive turbines and generate electric power.

Some still envision a 100-megawatt power plant – enough to power 80,000 homes – operating at South Meager Creek north of Whistler. But the cost of such a project, and some challenging geology, have made such a project impractical to date.

“At Meager, they found the high temperatures that they need, and there’s lots of water around,” says Woodsworth. “But the plumbing system is tight - there’s not a lot of fractures – so you really can’t get the plumbing system going to circulate the water.”

Clean Energy BC remains optimistic about geothermal’s role for future electricity generation in B.C., noting that BC Hydro has identified 16 prospective sites – including the South Meager Creek prospect - in B.C.

Other nations on the Ring of Fire are relying to varying extents on geothermal power for electricity, with the Philippines standing as the world leader in producing about 27% of their electricity from the earth’s heat. The largest group of geothermal plants in the world is located at the Geysers, a geothermal field in California.

Where to explore hot springs in B.C., and what you’ll see

Most of us get our first taste of a hot spring at one of the big commercial hot springs in B.C., such as Harrison in the Fraser Valley, or Radium and Fairmont in the Rocky Mountains. But Woodsworth is a huge fan of more natural springs, including several “wild” springs that are more difficult to get to.

One of his favourite hot springs is Hot Springs Cove off the west coast of Vancouver Island, and reachable only by boat or float plane. It’s a protected hot spring located on the ocean shore, where cold salt water mixes with the hot water from the spring to reach the perfect temperature.

To get to amazing Hot Springs Cove, on an island off the coast of Tofino, you'll need to hitch a ride on a boat or float plane.

To get to amazing Hot Springs Cove, on an island off the coast of Tofino, you'll need to hitch a ride on a boat or float plane.

(Photo copyright, Glenn & David Woodsworth)

This fall, Woodsworth will visit one of B.C.’s gems, Liard River Hot Springs, a more than 20-hour drive from Vancouver to a provincial park near the Yukon border. Liard is a great example of a hot spring whose warmth has created an ecosystem bursting with unusual plants and animals. including yellow monkey flower and the lake chub, a tiny fish unusual in that it can live in the hot water.

Main pool at northern B.C.'s astounding Liard River Hot Springs, which is a nearly 700 km drive northwest of Fort St. John.

Main pool at northern B.C.'s astounding Liard River Hot Springs, which is a nearly 700 km drive northwest of Fort St. John.

(Photo copyright Glenn & David Woodsworth)

“At many of these springs you find species which exist nowhere else in the world,” says Woodsworth. “At Banff, there’s a snail that’s found nowhere else in the world. At Liard, there’s fish there found nowhere else at that latitude.”

Woodsworth would like nothing more than to see some of B.C.’s kids emerge as amateur naturalists to help catalogue the flora and fauna (plant and wildlife) of B.C.’s hot springs. And he hopes that as many hot springs as possible will remain wild. One of his favourite hot springs, Sloquet, is reachable by rough dirt road at the upper end of Harrison Lake but is now too often populated by those more interested in selfies and beer drinking than the unique ecology of the place.

“If you’re going to go to Sloquet, don’t go up on a long weekend, and try winter when the road is closed,” he says. “Maybe try to ski in there in the middle of January when you’ll have it all to yourself. These things are often at their best in the winter because it may be snapping cold all around, but the area around the hot springs is often free of snow and you may even find the odd flower out. It’s a tiny, self-contained ecosystem.”

Additional maps & resources