Mountain snowpack plays a key role in B.C.’s hydroelectric generation

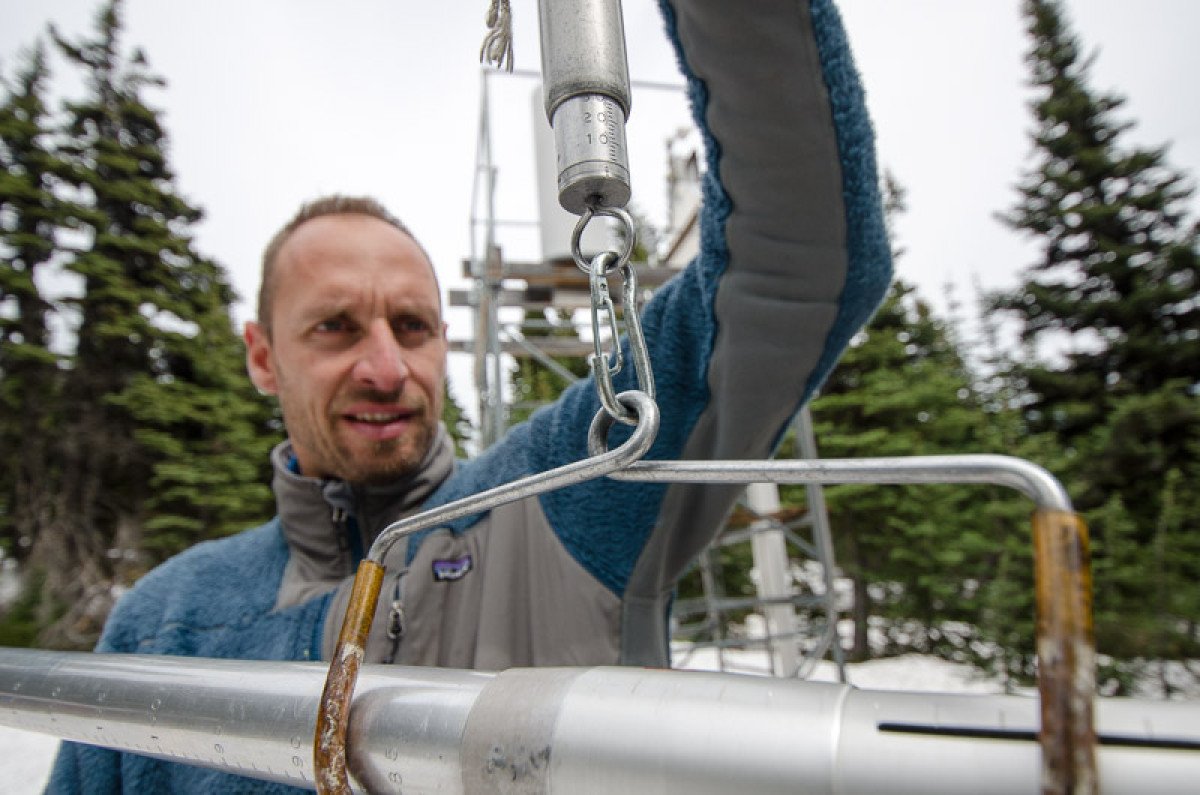

If you want to talk snow, Georg Jost is your man. Not only is he one of three hydrologists BC Hydro relies on to predict how B.C.’s mountain snowpack will translate into water for reservoirs, he’s an avid backcountry skier.

“I have a secret playground in the Ashlu Valley where nobody goes,” says Jost, almost in a whisper. “You drive into the Squamish Valley… and then go on a long, long hike with skis on your back – maybe three times the length of the [Stawamus] Chief hike - before you put your skis on snow. Then it’s amazing.”

Working out of Squamish, Jost is part of a BC Hydro team tasked with predicting – as accurately as possible – how much water will flow into BC Hydro’s reservoirs. Knowing how much water will flow, and when it will arrive in those reservoirs, is vital to energy planning.

“We basically estimate how much gas we have in the tank, and our energy planning group takes that information and decides what they’re going to do with that,” he says. “If we have lots of gas in the tank, our models will likely show we’re in a good position to sell power.”

Hydroelectricity’s big advantage is the ability to ‘store’ power

BC Hydro’s reservoirs can “store” massive amounts of water behind dams for electricity generation when we need it. Our large storage capacity allows us to hold back some of that water and generate power later, when there’s greater demand for that energy.

The ability to store power is one of the big advantages of hydroelectric dams over other renewable energy sources such as wind and solar, which generate power only when the wind blows or the sun is shining.

If we know how much snow melt coming a few months down the road, we can afford to lower our reservoirs in the short term by running water through turbines to generate electricity we can sell to the likes of Alberta or the U.S. The difference between a normal snowpack year and a warm winter with minimal snowpack can be huge. Rivers that normally run high into late June or even mid-July can slow to a trickle by early June.

While B.C.’s peak electricity demand is usually greatest during the winter months when energy is needed for heating and lighting our homes and businesses, some of our neighbours have high cooling demands (air conditioning) in the summer months.

For a hydrologist, snow melt is easier to predict than rain

In the two B.C. watersheds that feed BC Hydro’s biggest dams – notably GM Shrum in the north and Mica in the Columbia - melting snowpack accounts for up to 70% of the water that flows into reservoirs. That percentage is much lower in the Lower Mainland and on Vancouver Island, where rain accounts for about 70% of inflows to the creeks and rivers that feed our reservoirs.

Snowpack is a utility hydrologist’s best friend. Once you know snow depths, you can quite accurately predict what will happen once it melts and enters rivers feeding our reservoirs. The two the other contributors to BC Hydro’s reservoirs – rain and glacial melt – are a lot less predictable.

Rain can only be predicted about a week out, while glacial melt depends mostly on how hot a summer is. During a very hot summer, glacial melt can supply up to 40% of the inflows in August at Mica, even though the glaciers cover only 5% of the watershed. With the warming climate, glaciers are shrinking fast and in the future they won’t contribute as much water during summer as we have seen in the past.

“In the future, with climate change bringing warmer temperatures, you’ll have more precipitation in the form of rain and less as snow, which means it will be harder to predict inflows,” he says.

Climate change is also bringing more intense storms to B.C. The December storm that left thousands of British Columbians without power over the holidays was the most damaging storm in the province’s history, as more than 750,000 BC Hydro customers were left without power.

The outlook for this year? Normal to slightly below-normal snowpack in most of B.C.

BC Hydro’s hydrology data for winter 2019 showed snowpack levels in watersheds that feed our largest dams – in the north and in the northern Columbia – around normal. Snow levels across all of southern B.C. are lower than normal, in particular on the South Coast and Vancouver Island which are about 85% of normal.

What does that mean if you’re considering a spring break ski vacation? Big dumps of the white stuff in December and January had built a snow base of three metres or more at most mountains – and over six metres at Whistler-Blackcomb. But a cold, dry February didn’t add much snow to the mix, so skiers and snowboarders are looking forward to some much-needed new snow in the next few weeks.

Worried about climate change? The good, the bad, and the unknown

Jost underlines the importance of differentiating between what climate change will mean to electricity production in B.C., and what it will mean ecologically.

From a hydroelectric generation perspective, the science says there will be less snow and gradually less melt from shrinking glaciers – but more rain – in the coming decades. That means reservoir levels are expected to be as high, or even a bit higher, in the future.

But life in B.C., for the fish in our rivers, to the people in our cities, is changing with the climate.

“Forest fires in summer are almost a constant now, and only in recent years have we seen smoke in the sky in the Lower Mainland,” says Jost. “Glaciers are also going to retreat to 20% of what we have now, especially in the Interior.”

Ensuring that salmon and other fish in our rivers get the water they need may force BC Hydro to “spill” more water past our dams (rather than run in through turbines for electricity generation) at certain times of the year. And Jost imagines that from a skier’s perspective, he’ll be hiking further and higher up the mountain to reach backcountry terrain.

Asked if he has a message for kids wondering about what they might do to help fight climate change, he says the key is to maintain our connection with nature.

“Go out and look at nature and see how it changes and how it will affect things you do in your life,” he says. “See what mountains look like now, what glaciers look like, and experience it. Once you’re out in nature, then you can make your decisions.”

What did we learn from this story?

- In some areas of B.C., up to 70% of the water filling BC Hydro’s reservoirs is from melted snow.

- On the southern coast, the opposite is true, with about 70% of water in reservoirs coming from rain.

- It’s easier to predict the amount of water we’ll get from snowpack than it is from rain.

- If BC Hydro knows a lot of water will come from snow, we can lower reservoirs by using existing water to generate electricity.

- Storing water behind dams gives B.C. the advantage of storing water for when we need it most, on dark and cold winter days.

- In the near future, climate change isn’t likely to decrease water for hydroelectric power in B.C. While there will be less snow, there will be more rain.

- Climate change is already changing life in B.C., for fish and people alike. The most damaging storm in B.C. history, this past December, left more than 750,000 BC Hydro customers without power.