Salmon spawning season is upon us. In this post we'll highlight our new activity, bring attention to the Fraser River pink salmon migration, and highlight other resources to teach the importance of of salmon in our ecosystems with your students.

Our new Salmon Story activity

Our new Salmon story activity for grades K-3, created in collaboration with the Pacific Salmon Foundation, explores the life cycle of salmon. Students follow along and act out the journey of salmon from the riverbed to the ocean and back. The activity includes illustrated printouts of the salmon stages and habitat to help students engage with the story.

Pink salmon play out-sized role on the Cheakamus River

This could be a record year for the Fraser River pink salmon migration in B.C., with as many as 29 million fish estimated to enter the Fraser River system this August and September, along with huge numbers also expected to return to the Cheakamus River near Squamish.

It’s an odd-year natural wonder – the major pink runs in the area happen on odd years, including 2025 – for the smallest and least appreciated salmon species. But just because pink salmon are unlikely to be featured on the menu of your local restaurant – sockeye, chinook, and coho are much more popular – doesn’t mean they aren’t delicious. And just because they rarely grow above five pounds doesn’t mean they’re not prized by anglers or by those in the business of preserving fish habitat.

When the pink salmon spawn and die in the Cheakamus River, they not only leave fertilized eggs in the river bottom to keep the river-to-ocean-to-river cycle going, they’re also a vital protein-rich nutrient for eagles and other wildlife.

“Pinks are the biggest contributor to the overall health of the river system,” says Clint Goyette, a Squamish-area fishing guide and fervent advocate for pink survival enhancement on the Cheakamus. “Beyond the fact that as anglers we get to fish for adult pinks, the overall biomass they bring back from the ocean helps everything from bull trout and resident rainbow trout and cutthroat to eagles, bears, and other wildlife.”

There’s also evidence that plants along streams where salmon spawn benefit from the nutrients provided by the dying salmon. A study focussed on B.C.’s central coast and released in 2024 showed all plant species had higher salmon-derived nitrogen on streams with a higher spawning density, and that three of four species studied had larger leaves.

Like other Pacific salmon, pink salmon live most of their adult lives in the ocean. In saltwater they’re strong, silver-bright, and packed with fat and muscles and excellent eating. But when it’s time to spawn, they migrate back to the rivers where they were born.

Once in freshwater, their bodies start to change. Males develop hooked jaws (“kypes”) and humped backs, and both sexes stop feeding. They live off their stored energy while they fight currents, dig nests (redds), and spawn. Because they aren’t eating, their bodies weaken quickly. Skin darkens, flesh softens, and they begin to deteriorate. Within weeks of spawning, they die – that’s the natural end of their life cycle.

Anglers fish for pink salmon earlier in the migration, when the fish are still bright-silver and strong, before they’ve spent much energy traveling upriver. At that stage, they’re still healthy and good eating.

By March or April of 2026, millions of eggs from this fall’s run will hatch, with the salmon fry moving downstream, first to the estuary at the mouth of the Squamish River, and then out to the open ocean, where they’ll grow to between two and five pounds and return to spawn in the Cheakamus in 2027.

Did you know? September 28 was BC Rivers Day, with at least 50 events – including river cleanups, native plant planting, and a variety other family-friendly events – scheduled across B.C. Keep your eyes peeled for events next year.

Daisy Lake Reservoir stores water to power 96,000 homes

For decades, BC Hydro’s Cheakamus generating station has been providing British Columbians with enough renewable electricity to power the equivalent of 96,000 homes per year.

Located 40 km north of Squamish on the unceded traditional territory of the Squamish Nation, Tseil-Watuth Nation, and Lil'wat Nation, the Daisy Lake Dam impounds water flowing south in the Cheakamus River creating Daisy Lake Reservoir. The water in Daisy Lake Reservoir takes one of two paths to the Squamish River. It's either released from the dam down a 26-km stretch of the Cheakamus River to its confluence with the Squamish River, or it's diverted through a tunnel that runs through Cloudburst Mountain to the Cheakamus Generating Station on the Squamish River.

We work closely with stakeholders on releasing water into the river

Fishing guide Goyette is among the many stakeholders who have helped BC Hydro develop a Cheakamus Operations Plan that has evolved significantly in recent years. The Squamish Nation also played an important role in developing this plan. As climate change increases the chances of major fall rainstorms arriving earlier (and with more rainfall) than in the past, we’ve fine-tuned the way we manage flows in the river.

If there are no big rainstorms during the pink spawning season – roughly mid-August into October – the pinks will likely go about their business of egg-laying without issue. But if big rains hit, some pinks could be stranded after water recedes and shallow, temporary channels dry up.

We’re doing everything we can to avoid that scenario. We’re getting better at monitoring the salmon, tweaking flow reductions known as “rampdowns” on the Cheakamus, and regularly updating the local community, Squamish Nation, and anglers on the river.

“We’ve seen dramatic improvement in what BC Hydro’s operations are doing on the river,” says Goyette. “There’s always room for improvement, but we're all learning as we go, including our understanding of how the fish behave in this changing climate.”

Educational resources for exploring fish and water in BC Hydro’s system

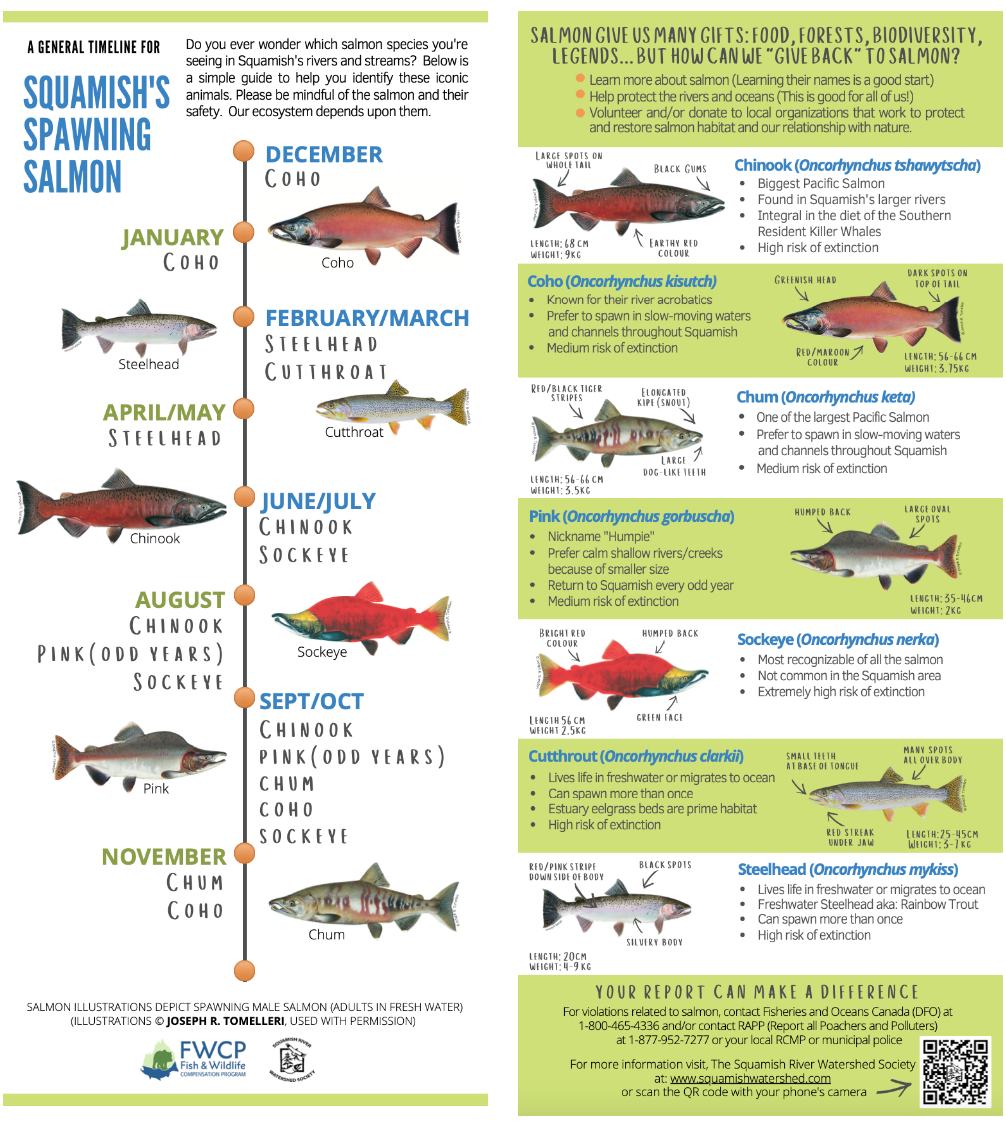

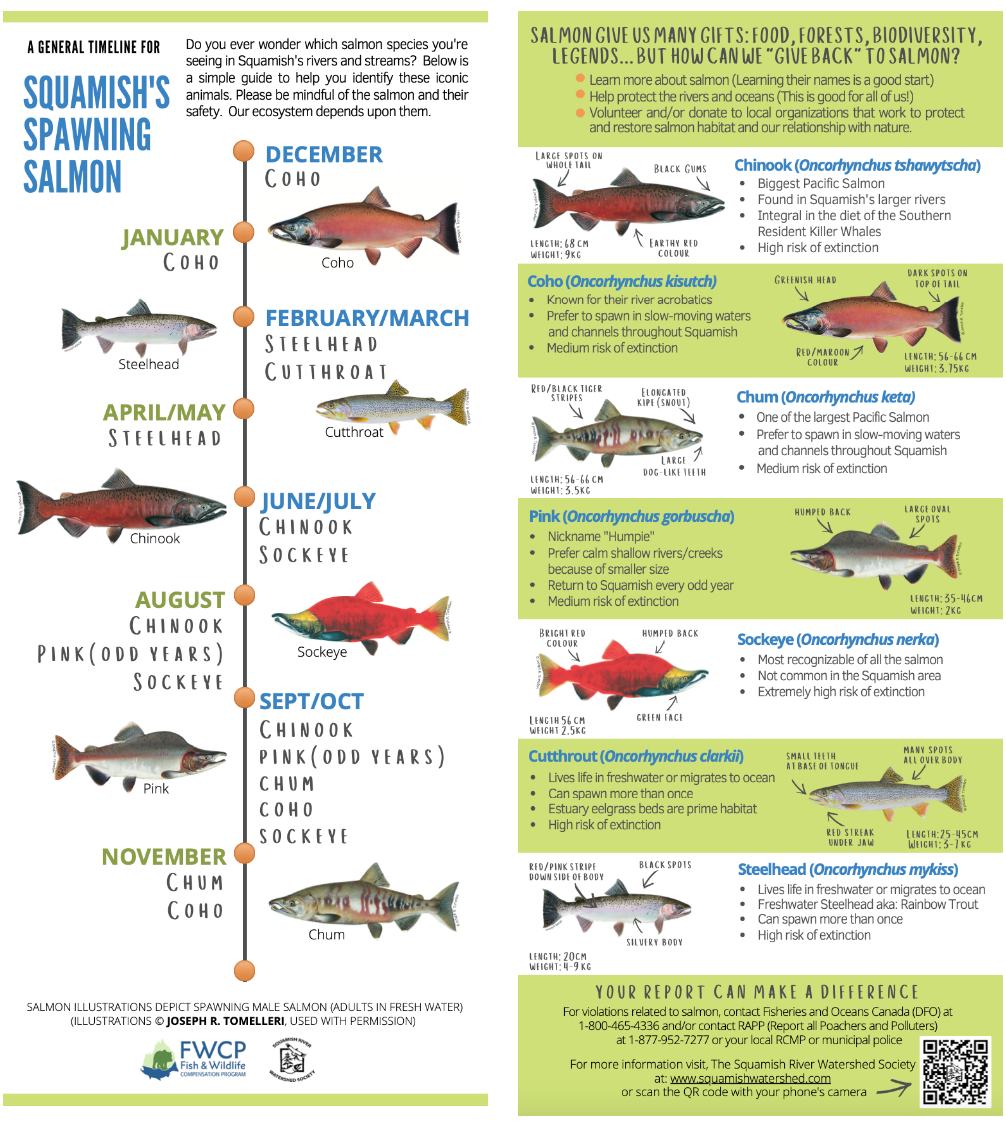

Here are some in-class activities that provide some context around the impacts to water and fish in BC Hydro's system, and our efforts to protect fish and water. For an excellent infographic on salmon migrating through Squamish, see the Squamish River Watershed Society’s Salmon in Squamish feature.

Salmon life cycle game (Grade 2)

The Salmon life cycle board game takes students on a salmon’s journey from the river to the ocean and back again.

Biodiversity and white sturgeon in B.C. (Grade 3)

Students discover through games, drawing and crafting, what a prehistoric white sturgeon is, and how we can protect this giant fish and other animals in our ecosystems.

Happy fish, sad fish game (Grade 3)

Students work in groups to learn about biodiversity in the local environment and gain knowledge of First Nations ecosystems with the endangered white sturgeon.

Ola's origami fortune teller (Grade 4-7)

Using Ola the orca’s water conservation tips as a thought starter, students play a word game, and make Ola’s origami fortune teller to play with their friends and share the conservation message.

Interconnected by water (Grade 5)

Students work in pairs to explore what Indigenous ways of knowing can teach us about how water interconnects all living things. Using a worksheet they create a web that accurately shows those interconnections.

Stewards of the water (Grades 5-6)

Drawing upon Indigenous perspectives and teachings, students describe what it means to be a good steward of the water.

Whose water is it? Card game (Grades 5, 6)

Students explore how water is shared between people and wildlife in B.C. through a card game.

Diverse perspectives of water (Grade 7-9)

Students work in groups to identify and apply additional perspectives and knowledge about water.

Drought, electricity and storm safety in B.C. (Grade 9)

students review how electricity in B.C. is generated using the power of falling water, how drought is impacting electricity generation and the effects of summer drought on winter storms and power outages.

Should water have rights? (Grades 10-12)

Inspired by Indigenous perspectives and referring to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, students explore the question of whether water should have legal rights.